LAWTON – Efforts to prevent crowding in the Comanche County Detention Center have frustrated the county commissioners and health officials for quite awhile.

But some degree of relief is on the horizon.

Before adjourning sine die last week, the Oklahoma Legislature adopted a Fiscal Year 2022 budget that includes increased funding for the Oklahoma Indigent Defense System. OIDS is the statewide agency that provides legal representation to clients throughout the state who have few, if any, financial resources.

The agency received a 17% budget increase for next year: from $17.5 million to more than $20.5 million, said Tim Laughlin, executive director of OIDS. The agency’s new budget includes $700,000 to establish a satellite office in Lawton, he told the Ledger.

The agency has eyed several properties in Lawton and expects to pick one for its office soon, Laughlin said. They also plan to hire six attorneys, an investigator and a secretary. “We want to be up and running by July 1,” he said; a deputy division chief will be the supervising attorney of the office.

“Our biggest challenge will be finding lawyers,” Laughlin said. Because of the landmark U.S. Supreme Court decision last July in McGirt v. Oklaho- ma, “We are competing with the feds and the tribes for attorneys and investigators.”

The Lawton attorney who provides indigent defense services in Comanche, Stephens, Cotton and Jefferson counties did not offer to renew her contract with OIDS for Fiscal Year 2022, which starts July 1.

The agency advertised the position and encouraged attorneys to bid for the job, Laughlin said. One bid was received: $750,000. “We realized we could open an office for about the same price,” he said.

The OIDS board rejected the bid and advertised the post again. The board received a $50,000 bid for Cotton and Jefferson counties, and awarded that contract to Toni Himes Capra, the town attorney for Medicine Park, Laughlin said.

That left Comanche and Stephens counties. One bid was received, $285,000 for Stephens County, which the OIDS board rejected, he said. Instead, Stephens County “is going to be covered by attorneys from the Lawton office,” Laughlin said.

COUNTY JAIL OVER CAPACITY FOR MANY YEARS

The satellite Indigent Defense office in Lawton is welcome news for Comanche County Commissioner Johnny Owens, whose Central District encompasses the Comanche County Detention Center in downtown Lawton.

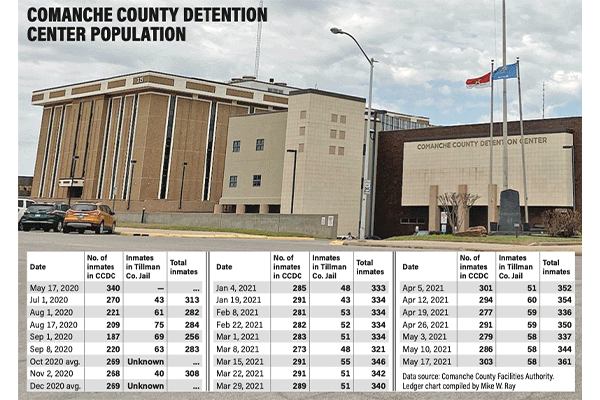

The CCDC has exceeded its authorized capacity of 283 detainees almost continuously for at least 14 years. For example, the jail held 340 detainees on May 17, 2020, and 303 one year later, on May 17, 2021.

The county routinely exceeded the State Health Department’s capacity limit for years, until a massive coronavirus outbreak a year ago infected more than 125 inmates and staff members.

Prior to the COVID-19 outbreak, the detention center was “always 60 to 80 detainees over” its authorized limit, Administrator Bill Hobbs told the Comanche County commissioners.

Then-State Health Commissioner Gary Cox issued a quarantine order against the CCDC on May 16, 2020. Under the terms of that order, the county was instructed to suspend acceptance of new inmates until the commissioner “determines the individuals under the quarantine” in the CCDC are no longer deemed by the commissioner to be “a threat to public health...”

The Oklahoma State Department of Health finally lifted the quarantine order more than three months later, on Sept. 2, 2020.

However, Barry Edwards, manager of the OSDH Detention Program, directed Hobbs to “identify to the [OSDH] your plan to address the relocation of inmates in an amount sufficient to correct” the overcrowding.

Edwards also limited the jail to no more than 95% of its rated capacity, or 269 detainees. The unused space was intended to remain in reserve should the need to quarantine inmates arise again because of another health crisis, Hobbs said.

CCDC OUT OF COMPLIANCE AGAIN THIS YEAR

The CCDC complied with the quarantine order and limited the inmate population for seven and a half months, but the jail has been out of compliance continuously this year – from as few as four inmates to as many as 34 over the permissible limit – as the accompanying chart shows.

Meanwhile, Comanche County has ‘outsourced’ dozens of its detainees to the Tillman County jail since mid-May of last year, at a cost of $45 per inmate per day. Invoices from May 2020 through April 19, 2021, totaled $684,810, ledgers show.

The Tillman County Jail, built in 1999, has sufficient space to accommodate Comanche County’s needs so far. The Frederick jail has a maximum capacity of 107 detainees, Administrator Mike Logan said. Tillman County can take up to 80 prisoners at a time from Comanche County, Hobbs said last year. “That leaves room for 27 for us,” Logan confirmed.

The daily average inmate population at Frederick hovers around 10 or 15, but recently it increased to 17-22, Logan said. “Things picked up and we’ve had a few with mental problems, too.”

Even so, “We try to keep space for at least 60 from Comanche County,” he said. “We need contract beds more than anything.”

“Part of our problem is people doing crazy stuff,” Commissioner Owens said.

For example, the jail is typically packed on Mondays with rowdy weekend revelers.

But the biggest problem, he said, is impoverished defendants. “We’ve got a backlog of them. Are fines too high? Is bail too high? I’m sure some of these people can’t afford the fines that are assessed against them, or they can’t afford their bail.”

POOR PEOPLE ‘HAVE A RIGHT TO REPRESENTATION’

Poor people “have a constitutional right to legal representation,” OIDS exec Laughlin said. “It’s our responsibility to provide that counsel.”

In areas where the Indigent Defense System has satellite offices, “We tend to keep the jail populations as low as possible,” he said.

“We meet with our clients at the jail and try to fashion bond reductions or to encourage alternatives such as pre-trial release programs. We meet our clients early and often and meet with the district attorney to get sentencing recommendations and alternative sentencing recommendations. We also limit continuances prior to preliminary hearings.”

OIDS public defenders “try to aggressively push cases forward so our clients are not just sitting in jail,” Laughlin said. “Bail doesn’t always have to be set at the highest possible level. We need to balance the nature of the crime and the circumstances.”

In 2018, the median “jail stay” of inmates in the Comanche County Detention Center who were accused of non-violent offenses and couldn’t afford to post bail was 120 days, according to Open Justice Oklahoma.

IF YOU HAVE THE ANSWER, ‘STEP UP’

The Comanche County Detention Center is “a holding facility,” Owens said. “We’re not a prison.”

Getting detainees “in and out” of the CCDC involves coordination among the district judges and the district attorney’s office and others, the commissioner said. As an example, “We have to take prisoners from the City of Lawton. Their municipal court is not a court of record. So if they arrest somebody for DUI, they have to bring him to us,” he said. “COVID-19 hasn’t helped either,” Owens added.

“We try to keep an eye on the jail,” Comanche County District Judge Emmit Tayloe said. “Every morning we get a text from the jail. But there’s only so much we can do.”

Because of the jail circumstances, Special District Judge Susan Zwaan said defendants who appear before her on misdemeanor charges “are more apt to be released on an OR bond.” That means the defendant is released by signing his/her name, without having to post a cash bond.

“We work on this issue constantly,” Owens said. “It’s the system. If somebody can give me the answer, step up.”