AFTERMATH OF McGIRT DECISION

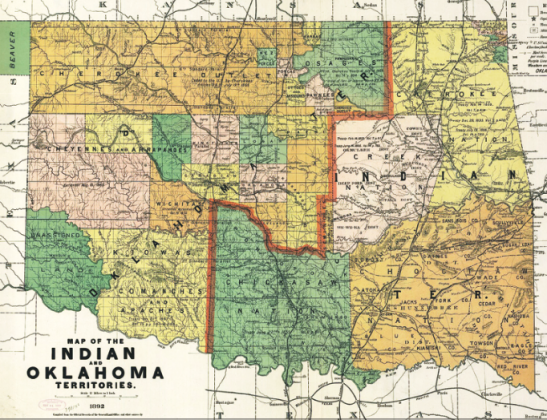

LAWTON – The U.S. Supreme Court, in its landmark McGirt decision announced in July, declared that Congress never disestablished the Muscogee (Creek) Nation’s reservation which encompasses portions or all of 11 eastern Oklahoma counties.

State district court judges have since ruled that no evidence has been presented to indicate Congress dissolved the Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw or Seminole reservations in eastern and central Oklahoma, either.

Consequently, major crimes committed by or against Native Americans within the boundaries of those five reservations must be prosecuted in federal rather than state courts, judges believe.

The status of the Kiowa/Comanche/Apache (KCA) Reservation in southwestern Oklahoma, though, is entirely different, state Attorney General Mike Hunter contends.

All of the Five Tribes and “potentially some of the other tribes throughout Oklahoma have unresolved reservation boundary issues,” Stacy Leeds, a recently appointed district court judge for the Muscogee (Creek) Nation, told KOSU public radio.

“You’re going to see McGirt play out in each of the tribes,” she said. “But they all have slightly different language in their treaties and their allotment agreements,” said Leeds, a Cherokee Nation citizen and a professor of Indian Law at the University of Arkansas. “And although the federal statute tends to apply to all Five Tribes, there’s still some very tribally specific distinctions.”

The status of the KCA reservation has arisen in at least four criminal cases pending in Comanche County, and was addressed by a Comanche County judge in a case that was appealed two years ago.

KCA RESERVATION STATUS IN QUESTION

Two killers who claim to be Native Americans assert that they were wrongfully prosecuted in a state court and their convictions should be vacated.

The Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals in September remanded their cases back to Comanche County for district judges to determine whether the defendants are indeed Native Americans and whether the crimes of which they were convicted occurred in Indian Country.

Comanche County District Judge Emmit Tayloe initially scheduled an evidentiary hearing on November 24 for Mica Alexander Martinez and Joshua Tony Codynah, both of whom were convicted of murder in Comanche County.

However, Tayloe scrubbed both cases from his docket temporarily, and indicated they may not be heard until January or perhaps even later.

He postponed the two cases at least in part because of the coronavirus, which has afflicted the county’s judiciary and resulted in closure to the public of the county courthouse in Lawton until at least January 4, 2021. The victims’ families informed Tayloe they want to attend the hearings, the judge told the Ledger.

Attorneys for Codynah and Martinez maintain that the KCA Reservation encompasses seven counties, “including the entirety of Comanche County,” and has never been dissolved by Congress. Attorney General Hunter disagrees and cites the Congressional Record in his legal brief to the court.

RECORDS INDICATE KCA RESERVATION DISSOLVED IN 1900

In 1900 the Kiowa, Comanche and Apache Tribes agreed to “cede, convey, transfer, relinquish, and surrender, forever and absolutely, without any reservation whatever, express or implied, all their lands...” and to “abandon” said lands, Hunter wrote. “This is exactly the kind of explicit language the Supreme Court in McGirt required to show disestablishment of a reservation...”

In McGirt, the Supreme Court held that “[t]o determine whether a tribe continues to hold a reservation, there is only one place we may look: the Acts of Congress.”

Hunter cites an Act of Congress dated June 6, 1900. “The land described as ceded in the 1900 Act is the same geographic description contained in Article II” of the First Treaty of Medicine Lodge Creek, dated October 21, 1867, which created a reservation for the Kiowa, Comanche, and Apache Tribes. That land constitutes “the entire reservation,” he writes.

The United States agreed to pay the tribes $2 million for the “cession of territory and relinquishment of title, claim, and interest in and to the lands as aforesaid...” The Act also refers to the land as being “abandoned by said Comanche, Kiowa, and Apache tribes...”

Hunter writes that the 10th Circuit Court of Appeals held that the 1900 Act “disestablished the organized reservation” and that the reservation was “dissolved”.

The Attorney General also noted that Comanche County District Judge Scott Meaders ruled two years ago, in an appeal from a man who pleaded guilty in 2005 to armed robbery of a Lawton restaurant and was sentenced to 20 years in prison, that the KCA reservation was disestablished.

DA SEEKS GUIDANCE FOR DEFINING ‘INDIAN’

Greg Mashburn, the district attorney for Cleveland County, filed a document on November 4 in which he asked the state Court of Criminal Appeals to provide some guidance on how courts can determine whether someone truly is an Indian.

In order to qualify as an “Indian” for purposes of invoking an exception to state jurisdiction, he wrote, a defendant must prove two facts/prongs: that he/she has “some, or a significant percentage of, Indian blood,” and the individual is recognized by a tribe or the government as an Indian.

The U.S. Supreme Court “has established that a determination of ‘Indian’ blood is a factor in determining Indian status,” Mashburn wrote.

“[T]his is a question this court must address” in light of claims filed by Shaun Michael Bosse and other defendants throughout Oklahoma “involving a large range of blood quanta.” Bosse, a white man, was convicted of murdering a Native American woman and her two children near Purcell, in Indian Country.

“[T]here does not appear to be a universal standard specifying what percentage of Indian blood is sufficient” to justify the first prong Mashburn referred to, because different jurisdictions “employ differing adjectives for the degree of Indian blood” – referring to “some” Indian blood, “sufficient” Indian blood, “substantial” Indian blood, or “significant” Indian blood.

WHAT PERCENTAGE OF INDIAN BLOOD WOULD BE SUFFICIENT?

“Courts have trended toward a minimum quantum of 1/8, or 12.5%, Indian blood,” the prosecutor wrote. During Bosse’s evidentiary hearing in McClain County, Judge Leah Edwards was informed that the two children Bosse murdered had 23/256 (approximately 8.9%) Indian blood quantum, and their mother had 23/128 (approximately 17.9%) Indian blood quantum. All three were enrolled members of the Chickasaw Nation.

“The State does not advocate a particular blood quantum” for categorizing a person as an Indian, Mashburn told the Court of Criminal Appeals. “Nor does the State seek to define who is, or is not, Indian for any purpose other than criminal jurisdiction.”

Instead, he asked the appellate court to decide “what, if any, threshold blood quantum” is required to establish Indian status “and whether the blood quanta at issue” in the Bosse case is “sufficient to satisfy that standard.”

Leah Edwards, a district judge for Garvin and McClain counties, ruled on October 13 that Bosse’s three victims were Indians and the crimes for which he was convicted “occurred in Indian Country for purposes of the General Crimes Act...”

Mashburn requested guidance from the Court of Criminal Appeals “to promote consistency with other courts and avoid a jurisdictional loophole...” Otherwise, a defendant could have his state court conviction vacated but later successfully argue in federal criminal proceedings “that he is not ‘Indian’ due to a low blood quantum and thereby escape justice,” Mashburn explained.