OKLAHOMA CITY – The ongoing legal battle between the Oklahoma Branch of the American Civil Liberties Union and the City of Oklahoma City over an anti-panhandling ordinance could prove costly for Oklahoma City residents after the United States Supreme Court refused to hear the case.

Earlier this week the nation’s high court shot down the city’s attempt for a hearing, known as a petition for certiorari.

Municipal attorneys filed the petition after a three-judge panel of the 10th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals ruled against Oklahoma City in August 2020. At that time a three-judge panel of the 10th Circuit said the city had “utterly failed” to justify its ordinance under the First Amendment.

“Objectively, medians share fundamental characteristics with public streets, sidewalks and parks, which are quintessential public fora,” the appellate court wrote.

Monday’s action by the U.S. Supreme Court upholds the lower court’s ruling.

That ruling, University of Oklahoma law professor Joseph Thai said, also paves the way for the ACLU to recover five years’ worth of legal fees in the case.

“Under federal civil rights law, the city has a responsibility to pay the attorneys’ fees of the victims whose rights they violate,” he said. “So they can’t complain that they’ve run up the tab by fighting tooth-and-nail to defend their odious ordinance.”

Thai said the high court action ends the debate over the ordinance. “We believed in our case. We believed in our cause. We’ve been vindicated.”

The fight over the ordinance has been long and contentious.

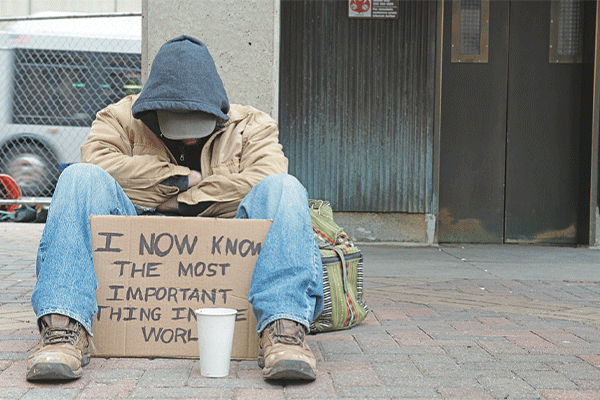

Adopted in December 2015, Oklahoma City’s anti-panhandling ordinance was authored by then councilmember Meg Salyer as a way to target panhandlers and others who used medians to solicit donations. The ordinance prevented the use of medians less than 30 feet in width and included an exemption for individuals responding to an emergency.

Persons found violating the ordinance could have faced a fine of $100. An earlier version of the ordinance levied a $500 fine and included possible jail time.

Records obtained from the City of Oklahoma City indicate that the ordinance was sparked, in part, by merchants’ complaints about homeless residents, particularly around the 23rd Street and Pennsylvania Avenue intersection.

Yet, even as they developed the ordinance, municipal officials were warned about the constitutional implications by their own attorney, Ken Jordan, and by representatives of the ACLU of Oklahoma.

In August 2015, Jordan wrote an email that questioned whether the ordinance would pass constitutional muster. “The downside of adopting additional panhandling soliciting regulations that could be unconstitutional would be a federal court lawsuit by the ACLU (or some other civil rights attorneys)

on behalf of panhandlers, for violation of their First Amendment rights since the right to beg or seek alms in a public place is First Amendment activity,” Jordan wrote.

The Neighborhood Alliance – a nonprofit organization that bills itself as an organization which helps “residents create sustainable change through our educational and support programs” also pushed for adoption of the ordinance.

Neighborhood Alliance executive director Georgie Rasco complained about panhandlers in a 2015 email, saying, “Panhandling first and foremost degrades the person who is relegated to standing on a street corner to ask for money. (It) hurts our businesses, our property values and perceived or real safety issues abound.” Rasco said many citizens in the area said “they no longer supported” the businesses at that intersection (23rd and Penn) due to alleged harassment from panhandlers.

“This clearly shows that the City of OKC needs to react to a serious problem,” Rasco wrote. “They cannot allow a small group of territorial panhandlers to ruin property values, devalue businesses and chase away a vital customer base.”

Yet, while the ordinance’s primary target was panhandlers, it also eliminated solicitations by firefighters, who frequently stood in intersections to ask for donations to the Muscular Dystrophy Association. The ordinance also eliminated access for protestors and for journalists who cover breaking news events.

Officials from the MDA wrote members of the Oklahoma City Council, telling them the ordinance would hamper their fundraising efforts by 75 to 80%.

Following those complaints, Salyer and other city officials put the ordinance on hold while they quietly negotiated a deal that would allow firefighters to solicit MDA funds in the parking lots of stores owned by Walmart.

Once an agreement with Walmart was reached, the city again ramped up its efforts to adopt the ordinance. At that point, city officials pivoted and began billing the ordinance as a public safety issue. In October 2015, Jordan sent another email, writing that city officials believed the ordinance to be constitutional, adding that the proposal didn’t target panhandling but was instead focused on public safety.

Oklahoma City adopted the ordinance on Dec. 8, 2015, by a vote of 7-2; councilmen Ed Shadid and Pete White voted no.

Thai, the law professor, said the action of the U.S. Supreme Court underscores the ACLU’s efforts. “It’s an important victory because it establishes that medians are free speech zones and have special protection under the First Amendment,” he said.

Still, Thai said he expects more legal battles in the future. He said ACLU officials would return to court soon seeking legal fees.

“We hope the city doesn’t fight,” he said. “But if it does, we will defend our client’s right to the fees.”