OKLAHOMA CITY – The state Conservation Commission is set to receive nearly $3 million from the federal government to help finance reclamation projects at abandoned coal mine sites in Eastern Oklahoma.

But the task is so large that it will take decades to complete.

In 16 eastern counties, state officials have identified more than 32,000 acres of abandoned surface coal mines and approximately 40,000 acres of abandoned underground coal mines, said Robert Toole of the Oklahoma Conservation Commission (OCC).

One reclamation project alone is estimated to cost $997,480, and the cost of another is $672,977, Toole said. Both of those abandoned coal mines are northeast of Porum, in Muskogee County. One project underway in Rogers County entails reclamation of a strip-mining pit on approximately 100 acres that will cost about $1 million to restore, Toole said.

“We have more than $120 million of unreclaimed abandoned mine lands still on inventory,” said Toole, director of the Conservation Commission Abandoned Mine Land (AML) Reclamation Program.

A typical reclamation project “will take about six years from identification to reclamation, pending no contingencies or environmental challenges,” he explained.

The order in which the projects are ranked is determined by a socio-economic matrix assessment, with public health and safety given the highest priority.

According to the Conservation Commission, more than two dozen people have died at abandoned coal mines in Oklahoma since 1972.

Despite the magnitude of the problem, Oklahoma is making headway. The Conservation Commission’s AML program has completed 190 projects and has restored more than 5,000 acres, Toole said.

SOME MINE SUBSIDENCES ARE HOLES IN THE GROUND...

Some mine cave ins appear as holes. Contractors typically fill the hole with large rocks, toss in some gravel to fill in the gaps, cap it with clay and a layer of topsoil then spread Bermuda sod over the site.

Some of those mines can be repaired in a relatively short time at minimal cost, but others are deemed to be critical and require immediate attention.

One such critical event occurred in April 2019 when an opening appeared just a few feet from the back door of a home in Tulsa. Soil and other natural material above an abandoned coal mine dropped into what appeared to be an abandoned mine room or entry that was close to the surface, according to the commission.

On Toole’s recommendation, the commission ratified an emergency declaration to repair the cave in as quickly as possible.

Private contractors made the repairs by filling the void with an estimated 12 cubic yards of flowable fill concrete, said Bryan Painter, the commission’s public information officer. The abatement project was completed within two days at a cost of $8,337, he said.

Also, in 2019, a sinkhole was discovered in a grade school playground at Haileyville in Pittsburg County. During spring break, the hole was filled and the site was revegetated with sod at a cost of $21,871.

Former state Rep. Donnie Condit of McAlester, a retired teacher, and school administrator, recalled a similar incident that occurred while he was the principal at Edmond Doyle School in McAlester.

“A parent came in the building early one morning and told me there was a hole by the front door. I went and looked at it and then called maintenance. They told me to use the wheelbarrow and haul some of the dirt from the new classrooms we were building on the other side of the building.

“So, I did, and when I emptied it into the hole it all went out of sight. I called maintenance back and said I didn’t have the time or strength to fill it. They brought a front- end loader, and it took four big loads to fill that hole. We didn’t bother to call anyone and report it. We had school going on! In north McAlester there are sinkholes and old coal shafts everywhere.”

...WHILE OTHER SITES COVER SEVERAL ACRES

Other reclamation projects are much larger and can cover several acres.

At one abandoned surface coal mine site northeast of Stigler in Haskell County, the operator carved out a gash in the land that extends for a mile, is more than 100 feet deep, and has filled with water to a level that’s deeper than all but about a dozen lakes in Oklahoma.

Toole recalled another site that’s a candidate for reclamation which involves eight property owners. To restore that land the OCC will have to secure property rights from all eight.

Some restoration projects involve multiple jurisdictions, Toole said, such as the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Native American tribes and county commissioners.

Sometimes the state Conservation Commission also must satisfy archaeological concerns or environmental issues such as the presence of the American burying beetle (which is considered an endangered species), the northern long-eared bat (also a threatened species), or nests of migratory birds.

Another reclamation project in Haskell County will require filling in a channel that’s about a quarter-mile long, Toole said. That job started in February and will take an estimated 11 months to complete, at a contract cost of $361,916.

Reclamation of a 16.5 acre aboveground strip mine in LeFlore County – one-half mile east of Rock Island and one-quarter mile south of SH-120, near the Oklahoma-Arkansas state line – took six months to complete, at a cost of $196,024, records show.

Toole said that restoration job entailed elimination of three hazards: a dangerous “In north McAlester there are sinkholes and old coal shafts everywhere.”

Donnie Condit Retired school teacher and administrator, and former state representative highwall (the unexcavated face of exposed coal in a surface mine), “spoil” piles, and three hazardous water bodies.

Earth fill employed in the reclamation project was calculated to be 89,446 cubic yards, he said. “All three water bodies were filled using the spoil pile material, which is essentially what came out of the pit area,” Toole said.

LOOK WHAT WE FOUND!

During reclamation of an abandoned coal mine site in Muskogee County, the contractor hired by the Conservation Commission discovered four vehicles – including a stolen van, a pick up, and a stolen speedboat – at the bottom of the water-filled channel.

OKLAHOMA HAD NO RECLAMATION LAW FOR NEARLY A CENTURY

Coal mining has been underway in Oklahoma since 1872, but no environmental reclamation laws were passed in this state until nearly a century later.

In 1968, the Open Cut Land Reclamation Act was passed, requiring producers to level only the tops of spoil ridges to a width of 10 feet. In 1971 the reclamation requirements were strengthened by requiring “a rolling topography traversable by machines or equipment commonly used with the land after reclamation.”

Conservation district directors, as well as other groups and citizens, believed that reclamation laws were still inadequate and therefore turned to Congress for assistance.

Then President Jimmy Carter signed Public Law 95-87, known as the “Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act of 1977.” That federal legislation established a nationwide system for controlling the surface effects of active coal mining and established a trust fund for the purpose of reclaiming orphan coal mine land that endangers public health and/or safety.

RECLAMATION FUNDS PRODUCED FROM FEE ON COAL MINING

Money for the Abandoned Mine Land (AML) Trust Fund is generated from a tax on active coal mining.

Oklahoma’s annual share of the federal funds is approximately $3 million. “We don’t have enough coal being produced in Oklahoma to get above what has been established as the minimum funding level,” Toole explained. Oklahoma is one of 10 minimum-program states “that have little or no coal mining anymore,” he said.

Oklahoma is considered a minimum program state because of its relatively small amount of current and historic coal production, he said.

The state Department of Mines reported 634,452 tons of coal were excavated in Oklahoma in 2017 (the latest year for which statistics are available).

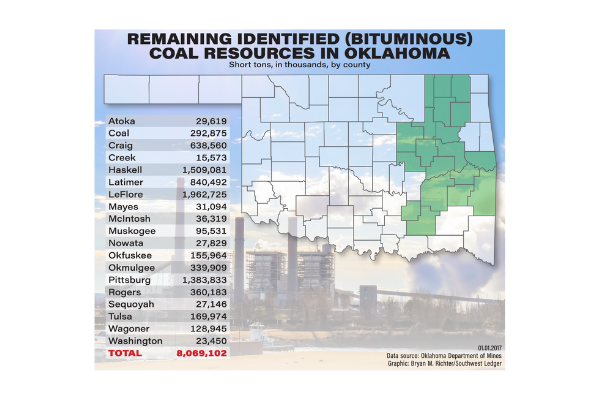

The 16 Oklahoma counties that previously had or still have coal mining operations are Lef lore, Pittsburg, Haskell, Muskogee, Rogers, Nowata, Craig, Mayes, Tulsa, Wagoner, Okmulgee, McIntosh, Sequoyah, Latimer, Coal, and Atoka.

FEDERAL ACT DUE TO EXPIRE, BUT RENEWAL BILL CLEARED FIRST HURDLE

The Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act gives the federal government the power to collect fees for AML funding, but that authority is scheduled to expire in 2021, Toole said.

However, a bill that would extend the program for another 15 years, and increase the federal contribution, passed the House Committee on Natural Resources on Jan. 15 of 2020 and awaits a floor vote in the U.S. House of Representatives.

H.R. 4248 would:

• Authorize the U.S. Department of the Interior to reimburse states and tribal governments for the emergency restoration, reclamation, abatement, control or prevention of adverse effects of coal mining practices;

• Extend the authority of the Interior Department to collect reclamation fees through Fiscal Year 2036;

• Increase from $3 million to $5 million funds that the Interior Department must award minimum program states (such as Oklahoma) and Native American tribes that have an approved abandoned mine reclamation program.

U.S. Rep. Markwayne Mullin, R-Westville, is a co-sponsor of the legislation. Mullin’s congressional district encompasses 14 of the 16 counties that have abandoned coal mines.